Ways to Improve Your Sleep

By Robin Sipp, MSPT, Clinical Director, Aquacare Lewes – Route 24

“The NSF has committed to regularly reviewing and providing scientifically rigorous recommendations,” says Max Hirshkowitz, PhD, Chair of the National Sleep Foundation Scientific Advisory Council. “The public can be confident that these recommendations represent the best guidance for sleep duration and health.”

The panel revised the recommended sleep ranges for all six children and teen-age groups. A summary of the new recommendations includes:

- Newborns (0-3 months): Sleep range narrowed to 14-17 hours each day (previously it was 12-18)

- Infants (4-11 months): Sleep range widened two hours to 12-15 hours (previously it was 14-15)

- Toddlers (1-2 years): Sleep range widened by one hour to 11-14 hours (previously it was 12-14)

- Preschoolers (3-5): Sleep range widened by one hour to 10-13 hours (previously it was 11-13)

- School age children (6-13): Sleep range widened by one hour to 9-11 hours (previously it was 10-11)

- Teenagers (14-17): Sleep range widened by one hour to 8-10 hours (previously it was 8.5-9.5)

- Younger adults (18-25): Sleep range is 7-9 hours (new age category)

- Adults (26-64): Sleep range did not change and remains 7-9 hours

- Older adults (65+): Sleep range is 7-8 hours (new age category)

How Exercise Helps You Sleep

It is not fully understood by researches how exercise improves sleep. Some things that have been verified is that exercise increases the amount of slow wave sleep you get.

Slow wave sleep has a direct correlation to deep sleep. Deep sleep is where the brain and body have a chance to rejuvenate. It is the time when your muscles repair and grow. Exercise can also stabilize your mood and helps to relax the mind. In turn, this cognitive process is important for naturally transitioning sleep.

How Diet Can Help You Sleep

If you want a good night sleep, one needs to emphasize a balanced diet to include fresh fruits, whole grains, and low-fat proteins. A diet low in fiber and high in saturated fats could take a toll on your sleep by decreasing the amount of deep, slow-wave sleep that you get during the night.

Be aware about the amount of sugar intake as well, too much sugar could result in wakeups during the night. Key vitamins are B vitamins which are found in fish, poultry, meat, eggs, and dairy. Research shows that B vitamins could help to regulate melatonin which is a hormone that regulates your sleep cycle. A proper diet can also control one’s weight. A reduction in body fat will make you less likely to struggle with sleep problems such as snoring, sleep apnea, insomnia, etc..

Reduce Spinal Pain by Targeting Changeable Risk FactorsConclusion

Spinal pain is a major and growing health problem with increasing rates of disability. (1) In the last two decades there has been an increase in imaging, opioid prescription, injections, and surgery with questionable benefit, (5-7) so it would make more sense to focus on the risks that can be changed.

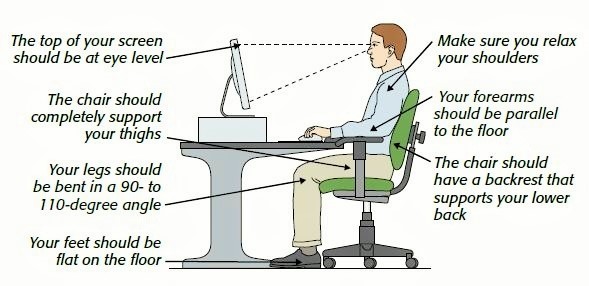

Changing physical risk factors like type of movement pattern, (8) level of strength and conditioning, (9,10) and sustained or repeated postures (11,12) are relatively risk free, cost effective, and show enormous potential.

Sleep posture is an example of a sustained physical risk factor that is modifiable. (64.65) Other modifiable risk factors are one’s diet and level of exercise. The impact sleep can have on one’s daily life is significant, especially with having the ability to modify a risk factor. Modifying risk factors can have one of the greatest impacts on the health of the spine, as well as the health of our mental wellbeing.

Sleep posture is not something one should just push aside along with the other low cost modifiable factors. The quality of sleep we get will have an huge impact on the overall quality of our lives.

Schedule your appointment today.

References:

1. Hurwitz EL, Randhawa K, Yu H, et al. The global spine care initiative: a summary of the global burden of low back and neck pain studies. Eur Spine J 2018;27:1–6.

2. De Koninck J, Lorrain D, Gagnon P. Sleep positions and position shifts in five age groups: an ontogenetic picture. Sleep 1992;15:143–9. 10.1093/sleep/15.2.143 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Haex B. Back and bed: ergonomic aspects of sleeping. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

4. Gordon S, Grimmer K, Trott P. Self-reported versus recorded sleep position: an observational study. The Internet Journal of Allied Health Science and Practice 2004;2:1–10. [Google Scholar]

5. Atlas SJ, Keller RB, Wu YA, et al. . Long-term outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of sciatica secondary to a lumbar disc herniation: 10 year results from the maine lumbar spine study. Spine 2005;30:927–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Friedly J, Chan L, Deyo R. Increases in lumbosacral injections in the Medicare population: 1994 to 2001. Spine 2007;32:1754–60. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3180b9f96e [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Runciman WB, Hunt TD, Hannaford NA, et al. . CareTrack: assessing the appropriateness of health care delivery in Australia. Med J Aust 2012;197:100–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. O’Sullivan P. Diagnosis and classification of chronic low back pain disorders: maladaptive movement and motor control impairments as underlying mechanism. Man Ther 2005;10:242–55. 10.1016/j.math.2005.07.001 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Gabel CP, Mokhtarinia HR, Hoffman J, et al. . Does the performance of five back-associated exercises relate to the presence of low back pain? A cross-sectional observational investigation in regional Australian council workers. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020946 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020946 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. . Micheo W, Baerga L, Miranda G. Basic principles regarding strength, flexibility, and stability exercises. PM&R 2012;4:805–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Solomonow M, Baratta RV, Banks A, et al. . Flexion-relaxation response to static lumbar flexion in males and females. Clin Biomech 2003;18:273–9. 10.1016/S0268-0033(03)00024-X [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Solomonow M, Zhou BH, Lu Y, et al. . Acute repetitive lumbar syndrome: a multi-component insight into the disorder. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2012;16:134–47. 10.1016/j.jbmt.2011.08.005 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Cartwright R, Ristanovic R, Diaz F, et al. . A comparative study of treatments for positional sleep apnea. Sleep 1991;14:546–52. 10.1093/sleep/14.6.546 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. van Maanen JP, de Vries N. Long-term effectiveness and compliance of positional therapy with the sleep position trainer in the treatment of positional obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep 2014;37:1209–15. 10.5665/sleep.3840 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]